WHITE PAPER

Introduction

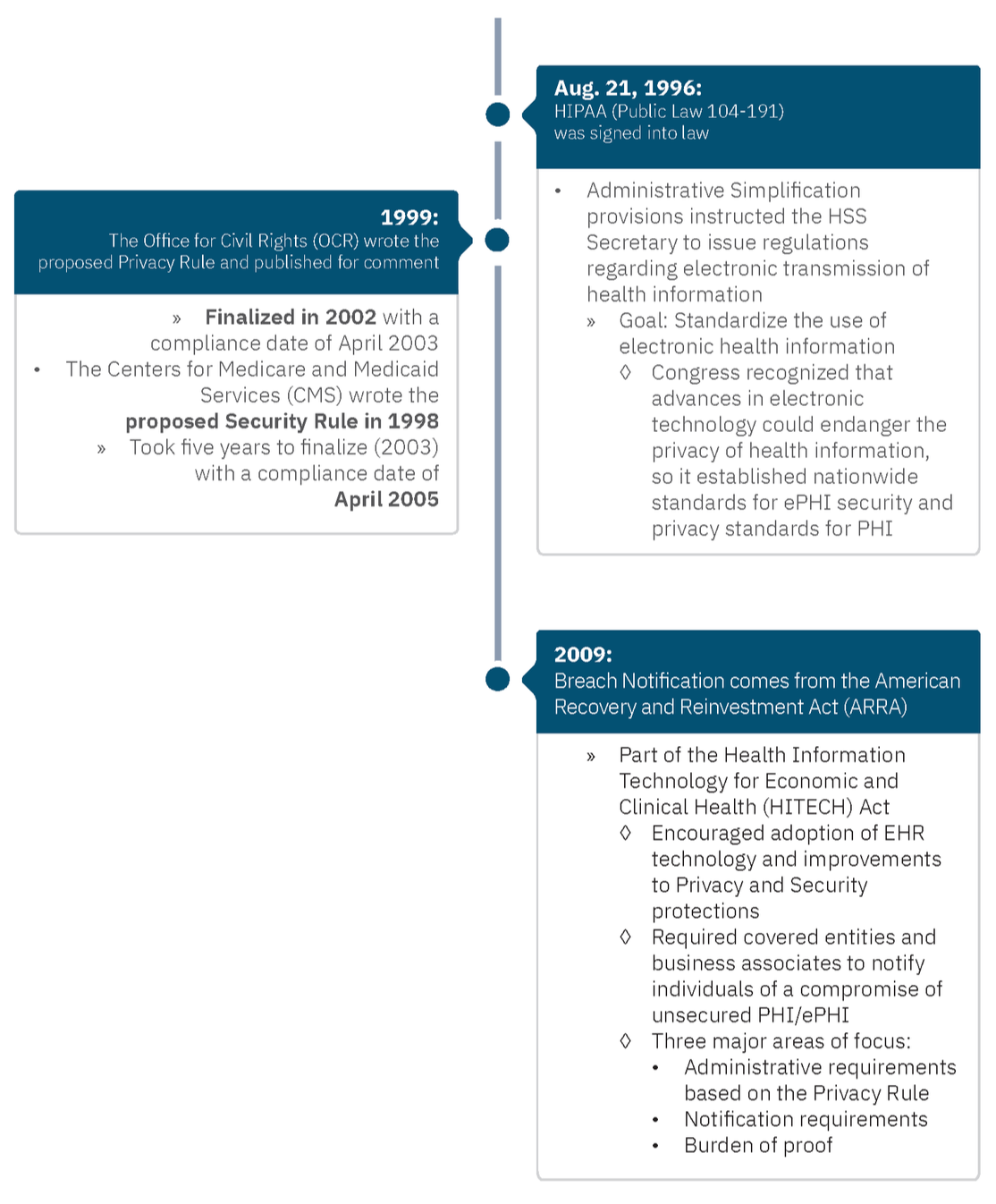

Since the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) became law in 1996, many healthcare organizations have struggled to fully understand and achieve compliance with HIPAA Privacy and Security mandates.

That may never be more true than now, especially post-pandemic, where healthcare organizations of all sizes are still trying to get their arms around all of the new technologies and digital health delivery models rapidly adopted over the past two years-and the associated threats and vulnerabilities that come with them.

It can feel even more daunting for business associates-many of whom are third-party vendors of software as a service (SaaS) or other digital applications and devices-and are, for the first time, entering into healthcare, unfamiliar with all of its requirements for protected health information (PHI).

Whether you’re a well-established healthcare covered entity that’s been effectively addressing HIPAA requirements for more than two decades or you’re new to healthcare as a business associate, it can be challenging to stay on top of HIPAA standards, especially as the threat landscape continues to evolve and the modern attack surface expands.

A Look Back

To understand HIPAA’s foundation, start with health insurance portability, looking all the way back to the U.S. Civil War, where what we might think of today as modern healthcare and health insurance got its foothold.

After the Civil War, employers, unions, and other organizations created “sickness funds,” where workers contributed about 1% of their wages. The funds would, in turn, provide about 60% of their wages to them if they became too ill or hurt to work.

This approach faced several challenges, and in the years that followed, various organizations tried to come up with different healthcare solutions, all of which had their own unique problems.

A key modern health insurance event occurred in 1974 with the passing of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA).

ERISA established a federal law with mandated standards to protect employees who use employee benefits, like health and retirement plans. It didn’t mandate that employees give workers health insurance, but it outlined how they would operate a health plan if they had one.

Before ERISA, many companies paid plan administrators, and their rates were based on an experience rating. So, for example, if employees for a particular company were deemed to be more susceptible to sickness or injury, they would have higher premiums.

However, ERISA enabled companies to be responsible for their own plans. It created an environment in which health insurance claims processing became more competitive. This happened simultaneously with the increased usage of computers. So, with lower costs associated with mainframe computing, more providers emerged to offer lower processing fees than larger insurance companies.

This eventually led to an increase in third-party administrators (TPAs) to process claims for employers.

While ERISA ushered in an era of competition, by the 1980s, the industry faced increased costs fueled by the adoption of new technologies and more cost-based reimbursements, which drove premiums up.

At the same time, in 1983, Medicare changed to a fixed price based on diagnosis-a direct correlation to some of what we see in healthcare today.

This was also when we saw the emergence of HMOs, formerly pre-paid health plans. HMOs began enrolling more subscribers and assumed responsibility for claims and underwriting.

As HMOs gained more ground, we saw the creation of new forms of managed care, such as:

- Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs): Health plans with medical contracts that set up a network of participating healthcare providers

- Point of Service Plans (POS): A hybrid of HMOs and PPOs where patients pay higher costs out of pocket to use non-participating providers

- Expansion of Medicare and Medicaid

By the 1990s, however, consumers pushed back against managed care plans, so companies made more efforts to negotiate lower prices. This is when we saw more provider consolidation and even the closing or mergers of hospitals to become larger hospital systems with reduced competition.

One of the key issues from this era was “pre-existing conditions.” Since the majority of health insurance was tied to employment, as individuals changed jobs and therefore changed insurance companies, insurers were able to refuse coverage for any condition that existed before coverage under the new insurer. This included conditions that had been covered by the prior insurer. A primary goal (it’s implicit in the name of the act) was to improve portability and reduce the potential for claiming an individual condition as uncovered, even though it was covered by another payor previously.

From History to HIPAA

When we think about HIPAA in a historical context, it becomes clearer why many of the key components are part of today’s law. They were designed to overcome many of the challenges healthcare insurance faced decades ago.

It provides a better understanding of the move for legislation to stop health plans from refusing to cover people in poor health, make it easier for people to maintain coverage during a job loss or change, and reduce healthcare fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA).

There are five Title areas of modern HIPAA:

- Title I: Insurance portability

- Title II: Fraud and abuse and medical liability reform, also administrative simplification

- Title III: Tax-related health provisions

- Title IV: Group health plan requirements

- Title V: Revenue off-sets

While all are applicable in terms of HIPAA compliance, what likely gets the most attention today are those administrative simplification components in Title II, which include privacy, security, electronic data interchange (EDI), and identifiers.

Why was administrative simplification needed? Healthcare is expensive to administer. Part of that cost was the result of the claims filing process pre-HIPAA. A range of people filed claims: individuals, hospitals, or providers, and often the individual insurers had their own forms and codes, which increased filing complexities.

This hodge-podge created deficits between payers and payees. So, the Administrative Simplification provision of HIPAA came about to standardize health industry transactions and code sets. This also coincided with the emergence of electronic health systems, enabling digital claims-filing, which ultimately moved us toward what we know today as healthcare covered entities.

Covered Entities

What is a covered entity?

In terms of HIPAA, a covered entity is a healthcare provider that conducts electronic transactions, as well as health plans and healthcare clearinghouses that conduct electronic transactions.

Not all healthcare providers are necessarily covered entities. Some providers choose to bill patients directly. If they don’t do this through electronic transactions, they’re not a covered entity, so HIPAA doesn’t apply.

However, all health plans have to be covered entities because they have to accept the transactions. Healthcare clearinghouses create, receive, maintain, or transmit PHI on behalf of a covered entity, making them a business associate and subject to HIPAA. Additionally, sub-business associates may be subject to HIPAA.

The Chain of Trust

When we think about these healthcare regulations, we should look at them through a chain-of-trust perspective.

Generally, the chain of trust begins with a HIPAA covered entity, for example, a hospital. The hospital has business associates, for example, third-party billing, legal services, or even a provider for their electronic health records (EHR). All those business associates may have sub-associates. For example, the EHR provider may contract with another company that provides access to the EHR portal.

At no point does the chain of trust stop existing between any of these different entities. Each one is responsible for PHI protections, and they must all operate within the scope of the business associate agreements they have in place.

The covered entity at the top of the chain of trust has the responsibility to ensure all the related requirements and restrictions are passed down to every business associate and sub-associate, ensuring the chain of trust stays intact at all times.

Basic HIPAA Requirements

Whether you’re a covered entity or business associate, some basic HIPAA requirements are applicable. Let’s look at them.

Administrative Safeguards

Based on 45 C.F.R. §164.308 Administrative Safeguards, a covered entity may permit a business associate to create, receive, maintain, or transmit electronic protected health information on the covered entity’s behalf. A business associate may permit a business associate that is a subcontractor to create, receive, maintain, or transmit electronic protected health information on its behalf. This must be done by a written contract such as a business associate agreement or another arrangement such as a memorandum of understanding or agreement. This is to ensure that an individual’s information is protected throughout that cycle.

When we talk about protected information, for HIPAA, that’s usually in regard to PHI, including:

- Past, present, and future mental or physical health or billing related thereto

- Can be connected to an individual by one of 18 identifiers

- All forms: Oral, written, electronic, etc.

- Excludes employment records and education records

Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification

There are three core pillars of HIPAA compliance: privacy and security, part of HIPAA, and then breach notification, which is part of the HITECH Act. The HITECH Act, passed in 2009, created a right for patients and third parties they designate to obtain their health information in an electronic format from providers who adopted a certified EHR. It expanded the application of HIPAA Privacy and Security rules to business associates, and perhaps most importantly, it started the Office for Civil Rights enforcement of the HIPAA Security Rule, which resulted in the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule[16] implementing breach reporting requirements, increasing enforcement, and increasing potential legal liability for HIPAA violations. Privacy, security, and breach notification were all codified with the Omnibus Final Rule, a final version of HIPAA published in the Federal Register on January 25, 2013.

The key to all three of these areas is the implementation specifications, meaning what you must do to ensure you’re compliant. Each area also has standards, which communicate at a higher level what you must do. Here’s what that looks like for each area:

- Privacy Rule

- 56 standards

- 54 implementation specs

- Security Rule

- 22 standards

- 50 implementation specs

- Breach Notification

- 4 standards

- 9 implementation specs

HIPAA isn’t generally considered prescriptive, meaning it doesn’t specify a methodology or technology. It instead leaves those decisions to the organization based on the size of the scope, resources, and other details.

Understanding the Privacy and Security Relationship

To be successful on your HIPAA compliance journey, it’s helpful to understand the relationship between HIPAA Privacy and Security.

HIPAA Identifiers

- Names

- All geographical subdivisions smaller than a state, including street address, city, county, precinct, zip code, and their equivalent geocodes, except for the initial three digits of a zip code, if according to the current publicly available data from the Bureau of the Census: (1) The geographic unit formed by combining all zip codes with the same three initial digits contains more than 20,000 people; and (2) The initial three digits of a zip code for all such geographic units containing 20,000 or fewer people is changed to 000.

- All elements of dates (except year) for dates directly related to an individual, including birth date, admission date, discharge date, date of death; and all ages over 89 and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age, except that such ages and elements may be aggregated into a single category of age 90 or older

- Phone numbers

- Fax numbers

- Electronic mail addresses

- Social Security numbers

- Medical record numbers

- Health plan beneficiary numbers

- Account numbers

- Certificate/license numbers

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers

- Device identifiers and serial numbers

- Web Universal Resource Locators (URLs)

- Internet Protocol (IP) address numbers

- Biometric identifiers, including finger and voice prints

- Full face photographic images and any comparable images

- Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code

Most organizations understand that HIPAA has a set of privacy principles and expects that your organization will manage the program. You must also:

- Give notice to the individual about how you use their information

- Give them choice and consent

- Let them know how you’ll collect, use, retain, and dispose of their information

- Explain how they can gain access to PHI

- Explain how their information will be disclosed to third parties

- Outline security controls to protect privacy and monitoring

All these elements align to achieve confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI.

Those same principles-confidentiality, integrity, and availability-also apply to HIPAA Security. The difference between these two rules is that privacy is overarching and affects all PHI regardless of source or time. Security is only for electronic protected health information (ePHI).

While it’s possible to have a security program without a privacy program, you can’t have a privacy program without a security program.

Why Are There Separate Rules?

When it comes to some of the ambiguity of HIPAA requirements, some organizations struggle because there isn’t a prescriptive framework that outlines specifically what each organization should do and how they must do so. That’s further complicated because these core areas are separated through three distinct rules.

Why are there three rules? In short, it boils down to timing.

Who Enforces These Rules?

In 2005, the HIPAA Enforcement Rule emerged after the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) discovered that many organizations were not complying with the Privacy and Security Rules. This gave HHS authority to investigate complaints and fine entities. HHS empowered the OCR for enforcement.

While OCR enforces HIPAA compliance, individuals have no private Right of Action. That means they cannot sue specifically under HIPAA law; however, state Attorneys General (AGs) can file civil suits on behalf of harmed residents.

The Journey to Compliance

The journey to HIPAA compliance centers around Privacy and Security (and Breach Notification) and relates to three keywords: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. But the biggest issue is risk identification.

In the context of PHI:

- Confidentiality: What happens if my sensitive information is shared?

- Integrity: What happens if my sensitive information isn’t complete, up-to-date, or accurate?

- Availability: What happens if my sensitive information is not there when needed?

Many organizations focus on confidentiality, but the other two components are just as critical.

Security Rule Highlights

The Security Rule has five general categories:

- Administrative safeguards (system access, network access, monitoring, logging, etc.)

- Physical safeguards (your physical security plan, badge readers, locked doors, etc.)

- Technical safeguards (encryption, data protection, devices, etc.)

- Organizational requirements (for example, how business associate agreements protect ePHI)

- Policies and procedures

These all apply to the protection of ePHI.

Required vs. Addressable Security Specifications

- Required Specifications, such as Risk Analysis, must be implemented as written. There is no flexibility to choose to not assess the potential risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of ePHI. The only flexibility is in the methodology used to assess the risks; however, the OCR published guidance describing their suggested method of doing so.

- In contrast, Addressable Specifications give some flexibility. Organizations are expected to:

- Assess whether each addressable implementation specification is a reasonable and appropriate safeguard in its environment when analyzed with reference to the likely contribution to protecting the entity’s ePHI and as applicable to the entity:

- Implement the implementation specification if reasonable and appropriate

- If implementing the implementation specification is not reasonable and appropriate, then document why it would not be reasonable and appropriate to implement it; and implement an equivalent alternative measure if reasonable and appropriate.

- Assess whether each addressable implementation specification is a reasonable and appropriate safeguard in its environment when analyzed with reference to the likely contribution to protecting the entity’s ePHI and as applicable to the entity:

Addressable does not equal optional.

The Privacy Rule

There are a significant number of requirements in the Privacy Rule, so that apply only to certain circumstance, but here we will focus on five key categories for the Privacy Rule:

- Uses and disclosures: Certain aspects of use are allowed by type (For example, who needs access to data to do their job to the minimum necessary standard, which roles need access to one data set versus another, etc.).

- Individual rights: For example, individuals can see or get a copy of PHI; can ask to change wrong information; know how their PHI is used or shared; request to restrict information they don’t want to be shared, or make requests for contacts in different places or different ways.

- Notice of Privacy Practices: Explain how PHI is disclosed and used, explain individual PHI rights, and summarize legal requirements for PHI.

- Organizational requirements – addressing how information is shared with business associates and protected in the process.

- Administrative requirements – including rules about managing the program, training, sanctioning offenders, and many others.

This covers all PHI, including ePHI.

The Breach Notification Rule

There are three primary requirements for the Breach Notification Rule.

- Administrative requirements: Points back to administrative requirements in the Privacy Rule, including sanctioning violators of the rule, training, and program management.

- Breach notification: How do I make a notice? In which circumstances must I make a notice? Whom must I notify? What must my notice contain?

- The burden of proof: If there is a compromise of health information, you maintain proof that you performed as risk assessment and determined the risk of exposure to be below a low threshold, or that you made notice..

This applies to all PHI, including ePHI.

Liability Beyond HIPAA

In terms of compliance, healthcare organizations give much-needed focus to HIPAA; however, other entities can also hold healthcare organizations accountable.

For example, the FTC launched an investigation into Flo Health because it was reported that it shared user health information with an outside data analytics organization after promising to keep it private. In the settlement, the FTC required Flo Health to obtain affirmative consent from users of its application before sharing PHI with others and also to get an independent review of privacy practices.

But liability goes beyond fraud and deceptive processes under the purview of the FTC.

For example, St. Joseph’s Health System faced a $2.1 million OCR settlement for issues where PHI was publicly accessible through the internet from 2011-2012. Still, that settlement was small in comparison to other penalties and fees. It also settled with a cash payment of $7.5 million to participating settlement class members. Court documents also indicate that St. Joseph spent an additional $7.5 million on identity theft protection, $13 million to institute policies to comply with federal and state regulations, and $7.5 million in attorney’s fees.

Accretive Health faced major consequences after an employee’s laptop, which contained 20 million pieces of information on 23,000 patients, was stolen from the employee’s car. As a result, the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office filed suit, resulting in a $2.5 million settlement. But the impact went even deeper. There was a class action lawsuit resulting in a $14 million settlement, which led to an FTC settlement as well…

While HIPAA compliance should remain a priority, other legal and regulatory requirements may apply to your organization, industry, or location.

The Three Ps for HIPAA Compliance

With insight into HIPAA basics, you may wonder what your organization can do to ensure you’re on the right path to compliance.

Regarding HIPAA compliance, HHS and OCR do not recognize any external organization’s “seal of approval” or “seal of compliance” for HIPAA compliance.

HIPAA compliance is not a certification. It’s about doing what’s expected all the time. Remember, it just takes one slip, one bad policy, to become out of compliance with an aspect of HIPAA requirements. Think of compliance in terms of a journey, not a destination.

If you really want to establish and manage an effective compliance program-whether for Privacy, Security, Breach, or all three, it takes commitment, energy, effort, and your organization must stay on top of it.

So, what are some things your organization can do to ensure you’re building an effective HIPAA compliance program that meets all Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification requirements?

It’s all about balance and starts with your policies.

Your policies define your organization’s values and expected behaviors. They establish “good faith” intent.

Procedures are your documented processes. They overview the required actions to deliver on your organization’s values. What are these steps? For HIPAA, if it’s not written down, it doesn’t exist.

To be effective, keep your policies and procedures updated and review them routinely. You’ll need to do this at least annually, but as best practice, any time your organization or systems change. This should be a continuous process. It’s not just about writing it once and hoping your employees will follow the rules.

People play a critical role in HIPAA success. It’s not just the people who write policies, publish the procedures, and train the staff. It’s also about management engagement. For example, do you have executive buy-in? Do you have the support of your C-suite, and are you working toward the same goals? Are your team members well-trained and aware of HIPAA requirements?

Remember, your training should not be generic or overly high-level. It should be focused on your policies and procedures. There’s no one-size-fits-all for most organizations or even all organizational roles. For example, what a front desk person who checks-in patients should know will likely differ from what a lab tech, nurse, or doctor needs to know.

And finally, stay focused on your safeguards. Your safeguards encompass all the things that go into PHI and ePHI protection, including various administrative, physical, or technical security controls.

For HIPAA compliance, it’s all about establishing reasonable and appropriate controls and safeguards for your environment, not for someone else’s.

Looking Forward

Looking at current trends, we’re optimistic that OCR will continue to provide guidance and support. While the agency gets much attention for its settlement actions, it isn’t just about enforcement and willfully charging organizations penalties while demanding settlement agreements.

OCR offers a range of guidance. The agency receives many complaints and conducts hundreds of reviews annually. Top issues will continue to receive attention. In 2021, those top issues included:

- Impermissible uses and disclosures

- Access

- Safeguards

- Administrative safeguards

- Breach notifications

We can expect to see other regulatory initiatives continue to garner attention as HITECH initiatives focus on recognized security practices and possible changes around civil money penalties and settlement sharing. There are also proposed changes to the Privacy Rule pending that won’t be fully known until the Final Rule is published.

In the interim, stay focused on HIPAA basics, and if you need help taking a closer look at your existing programs and how you can strengthen them, reach out to a Clearwater advisor, and we’ll be happy to help.

About Clearwater

Clearwater is the leading provider of Enterprise Cyber Risk Management and HIPAA compliance software and consulting services for the healthcare industry. Our solutions enable organizations to gain enterprise-wide visibility into cybersecurity risks and more effectively prioritize and manage them, ensuring compliance with industry regulations. Clearwater’s suite of IRM|Pro® software products and consulting services help healthcare organizations to avoid preventable breaches, protect patients and their data, and meet OCR’s expectations, while optimizing cybersecurity investments. More than 400 healthcare organizations, including 64 of the nation’s largest health systems and a large universe of business associates that serve the industry, trust Clearwater to meet their information security needs.